bplant.org Blog

Disturbance and its Role in Plant Habitat Preferences

May 29th, 2025 by Alex Zorach

A critical and often neglected aspect of plants' habitat preferences is disturbance. Broadly speaking, a disturbance in an ecosystem is an event that changes the environment, usually harming and/or killing some plants in the process. Some examples of disturbances include flooding, drought, fire, landslide, logging, or a wind storm.Disturbances can be natural or anthropogenic (human-induced), and some, such as those related to climate change, result from an interplay between natural and anthropogenic factors. Disturbances can cover all spacial scales, from micro-disturbances such as a small animal digging a hole or a large animal treading on soil with its hooves, through slightly larger ones like a tree or a few trees being thrown by a windstorm, to massive scales like a broad region experiencing drought or a major volcanic eruption.

This wildfire near Mountain Home, Idaho, illustrates the interplay between natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Although the ecosystems here would have burned naturally, the introduction of an invasive species, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), has altered the fire dynamics, extending the fire season as it dries out earlier than native grasses, and often leading to more severe fires. Photo © U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, CC BY 2.0, Source.

This wildfire near Mountain Home, Idaho, illustrates the interplay between natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Although the ecosystems here would have burned naturally, the introduction of an invasive species, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), has altered the fire dynamics, extending the fire season as it dries out earlier than native grasses, and often leading to more severe fires. Photo © U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, CC BY 2.0, Source.Disturbance is not inherently good or bad, but it does shape what plants can grow and thrive in a particular environment. And, in the long-run, disturbance plays a key role in creating and maintaining biodiversity.

Understanding disturbance is key for working with plants in any setting, whether in gardening, landscaping, ecological restoration, or conservation work.

Specific Plants have Specific Adaptations to Specific Disturbances

When looking at the variety of plants in our natural environment, a question that arises is: "Why are there so many species? What makes each one different?" One of the key answers is adaptation to different disturbance regimes. For example, among the white oak group, post oak (Quercus stellata) is adapted to withstand both severe drought and fire, and as such, it resists both.At the other end of the spectrum, bottomland oaks such as overcup oak (Quercus lyrata) are adapted to withstand flooding. Interestingly though, there are many different white oaks that grow in bottomlands. Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor) and swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) both are adapted to sites that flood less deeply than overcup oak. Overcup oak tends to grow on the lowest sites next to rivers, but it tends to grow on sites that flood primarily in late winter or spring. It leafs out significantly later than swamp white oak or swamp chestnut oak, allowing it to remain dormant during the period of most severe flooding. This adaptation allows it to inhabit lower, more flood-prone sites where those other two oaks could not survive. However, because it leafs out late, it has a disadvantage on slightly higher, drier sites, and these sites tend to be colonized by other oaks.

There are even white oaks adapted to both flooding and fire, such as bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa). Bur oak tends to be more common farther west, being dominant primarily in the Great Plains, from Texas north through KS, NE, MO, IO, MN, and surrounding states. This region is drier than regions to the east, so fewer trees at all are able to survive on uplands, with these sites instead supporting open prairie. And bottomland sites are such that they can be subjected to both flooding, and drought and wildfire.

This picture illustrates multiple fire adaptations of Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa). The thick bark insulates against fire. The distinctive leaf shape, with curving side-veins, makes dead leaves curl, causing them to sit upright on the ground. This leads the litter to dry out, even in the moist bottomlands where they occur. The dry litter promotes low-intensity ground fires, which protect the bur oak both by killing less fire-tolerant trees that might outcompete the bur oak, and also by removing fuel, so as to prevent more severe crown fire that the bur oak could not withstand. This mechanism is a key factor in the maintenance of bur oak savannas, common at the border of the Great Plains and Eastern Temperate Forests. Photo © Nathan Walther, CC BY 4.0, Source.

This picture illustrates multiple fire adaptations of Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa). The thick bark insulates against fire. The distinctive leaf shape, with curving side-veins, makes dead leaves curl, causing them to sit upright on the ground. This leads the litter to dry out, even in the moist bottomlands where they occur. The dry litter promotes low-intensity ground fires, which protect the bur oak both by killing less fire-tolerant trees that might outcompete the bur oak, and also by removing fuel, so as to prevent more severe crown fire that the bur oak could not withstand. This mechanism is a key factor in the maintenance of bur oak savannas, common at the border of the Great Plains and Eastern Temperate Forests. Photo © Nathan Walther, CC BY 4.0, Source.These examples explore only a single limited taxon of plants (the white oaks) and their handling of a single type of disturbances: those related to the presence or absence of moisture, i.e. the spectrum of flooding vs. drought and fire. There are countless other taxa and countless other types of disturbances. Thinking from this perspective, it becomes easier to understand how and why there are thousands of plant species native to North America, and sometimes dozens even within a single genus.

Adaptation to Disturbances Has a Cost

Every adaptation to a challenge has a cost. The overcup oak gives up a few weeks of photosynthesis as a trade-off to better withstand deep spring flooding. The post oak grows slowly so that its foliage is not overextended in a drought, and mature trees grow thick bark to insulate against fire.Plants that forgo these adaptations will have an advantage in a habitat free from these stressors. For example, each of the sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) are poorly-adapted to both drought or flooding, requiring mesic (consistently moist but well-drained) conditions to thrive. But by avoiding the costly adaptations to drought or flooding, these trees achieve greater photosynthetic efficiency, and are among the most shade-tolerant of all trees in Eastern North America. In the absence of disturbance, they eventually replace most competing trees. Even their associate, the yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), relies on sunnier gaps created by a small disturbance such as a single tree dying, in order to establish.

Another example of such tradeoffs is seen in milkweeds. Whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata) is a pioneer species that is among the first colonizers of sunny, dry sites with poor soil, where a disturbance has cleared all vegetation. Its narrow leaves with little surface area make it able to withstand drought stress even before it has had time to establish much of a root system. But these leaves cannot capture much sunlight, which not only limits it to sunny sites, but makes it less competitive against other vegetation. At the other end of the spectrum, poke milkweed (Asclepias exaltata) has broad, thin leaves that are both outstanding at capturing light and inexpensive to manufacture, allowing it to persist in shade. But the thin leaves leave the plant so susceptible to drought stress that it typically can only survive on sites sheltered from wind. A disturbance that removed too many trees would probably eliminate it from a site.

The narrow leaves of whorled whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), with little surface area, help it resist drought stress, allowing it to colonize dry, sunny sites with poor soil. But these leaves come at the tradeoff of making it intolerant to shade and competition. As such, its niche is limited to being a pioneer species on sunny sites. Photo © Jeremy Atherton, CC BY 4.0, Source.

The narrow leaves of whorled whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), with little surface area, help it resist drought stress, allowing it to colonize dry, sunny sites with poor soil. But these leaves come at the tradeoff of making it intolerant to shade and competition. As such, its niche is limited to being a pioneer species on sunny sites. Photo © Jeremy Atherton, CC BY 4.0, Source.The more one studies these matters, the more one realizes that the disturbances are inseparable from the plants. The adaptations to the various disturbances are reflected in the plant's morphology and behaviors (such as timing and growth responses) which in turn are encoded in the plant's genetics. To understand plants, you need to understand disturbances.

Learning the disturbances a plant is adapted to is as important as learning how to identify it by leaf or flower shape, and indeed, often goes hand-in-hand with learning its morphology because the morphology is an adaptation to its environment. And this is why, in our plant comparison and ID guides, you will find extensive discussion of disturbance and how the plant is adapted to it. Often, disturbance can be a key factor that can help you to identify a plant, as certain plants either will or won't be found on sites subjected to a particular type of disturbance. Understanding the relationship between adaptation and morphology can also help you remember how to identify a plant.

Periodic vs. One-time Disturbance & Succession

Disturbances can be periodic, and the degree of regularity of periodic disturbance can also vary. It is common for some rivers and streams to flood periodically, often in spring. At the same time, the severity of flooding may vary greatly from one year to the next. Drought and fire can also be periodic, but also vary both in intensity and frequency. When disturbance is frequent and regular, it creates a plant community adapted to the disturbance. These communities may include long-lived perennials or woody plants able to survive through the disturbance many times, and also annuals, biennials, or short-lived perennials that quickly germinate following the disturbance.One-time or rare disturbances create a different sort of environment. A rare disturbance will often kill most or all of the plants in an ecosystem, resetting the ecosystem back to a more barren state in which plants need to recolonize gradually. In some cases, such as when soil was washed away by a flood or landslide, severely burned by fire, or covered in a lava flow, the soil itself may need to accumulate or develop. Plants adapted to rare disturbances may exhibit traits such as long-term seed banking (common in legumes) or off-site dispersal (such as wind-, animal-, or flood-dispersed seeds) so they can establish on a site where all the vegetation has been removed.

This savanna of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) in North Carolina is a habitat that experiences regular fire; the regularity of the fire keeps the understory open, and limits fuel accumulation so that the fires are usually not severe enough to harm the mature trees. Such a fire regime is typical in the maintenance of savannas. Photo © John Kees, Public Domain, Source.

This savanna of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) in North Carolina is a habitat that experiences regular fire; the regularity of the fire keeps the understory open, and limits fuel accumulation so that the fires are usually not severe enough to harm the mature trees. Such a fire regime is typical in the maintenance of savannas. Photo © John Kees, Public Domain, Source.The schedule or pattern of disturbance is not a function of the type of disturbance alone; the same type of disturbance can be regular in one environment and rare in another. For example, Florida scrub communities would naturally experience fire almost every year, triggered by lightning strikes at the end of the dry season. Because the fire is frequent, fuel accumulation, and thus fire severity, was limited. These communities support trees such as sand pine (Pinus clausa) and longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) that can survive such fire. On the other hand, Chaparral in the California Coastal Sage, Chaparral, and Oak Woodlands tends to experience infrequent, severe fire after years or even decades of fuel accumulation. Here fire kills almost everything, leading to a process where the plants gradually recolonize.

The process through which an ecosystem regrows following a major disturbance is called succession. The term succession is not used for regular disturbances, only rare, catastrophic ones. Early in succession, pioneer species colonize the site. Part of a plant's habitat preferences include which successional stages of the habitat it occurs in. For example, the red mulberry (Morus rubra), which grows in floodplain forests, typically shows up around 80-90 years after a major disturbance. These forests may experience flooding nearly every year, but these disturbances are not severe and generally leave most of the forest intact.

"Succession" typically refers only to catastrophic disturbance. The red mulberry (Morus rubra) typically only shows up in late-successional stages in bottomland forests, but here "succession" is understood to involve the establishment of trees able to withstand whatever regular disturbances, such as temporary flooding, the forest is subjected to. Note that this mulberry is much younger than the canopy trees.

"Succession" typically refers only to catastrophic disturbance. The red mulberry (Morus rubra) typically only shows up in late-successional stages in bottomland forests, but here "succession" is understood to involve the establishment of trees able to withstand whatever regular disturbances, such as temporary flooding, the forest is subjected to. Note that this mulberry is much younger than the canopy trees.Photo © Siddarth Machado, CC BY 4.0, Source.

Disturbance in Gardens and Managed Landscapes

Gardens and managed landscapes are subjected to regular, often heavy anthropogenic disturbance, which we can think of as managed disturbance. Mowing, weed-whacking, mulching, weeding, and herbicide use are some of the most common examples of disturbances that humans carry out on managed ecosystems.If you want plants to thrive in a managed landscape, you need to choose plants adapted to whatever disturbance regime you are carrying out on that landscape. For example, if you want plants to grow in a regularly-mowed lawn, they need to be adapted to mowing. Some native grasses, such as poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata), nimblewill (Muhlenbergia schreberi), and buffalo grass (Bouteloua dactyloides), can survive and thrive in lawns, as can some broadleaf plants, like the introduced white clover (Trifolium repens), or the native common blue violet (Viola sororia) or marsh blue violet (Viola cucullata). These broadleaf plants, however, will not survive in lawns treated with selective herbicides like triclopyr or 2,4-D.

Tilling or cultivation of soil is another type of disturbance, in which all of the surface soil on a site is agitated and mixed. Tilling tends to kill certain types of plants, while favoring others. Tilling usually promotes annuals by giving their seeds a space to germinate, whereas refraining from tilling favors perennials. However, shallow tilling can favor perennials with deep rhizomes, such as the persistent invasive japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense), or common mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris), as well as some native plants with similar growth habits such as tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima) or common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca).

This photo shows hairy crabweed (Fatoua villosa) seedlings that have sprouted in exposed soil in a garden. The act of weeding continuously disturbs the soil, providing ideal habitat for such plants with short lifecycles that like exposed soil. Photo © Emily Summerbell, CC BY 4.0, Source.

This photo shows hairy crabweed (Fatoua villosa) seedlings that have sprouted in exposed soil in a garden. The act of weeding continuously disturbs the soil, providing ideal habitat for such plants with short lifecycles that like exposed soil. Photo © Emily Summerbell, CC BY 4.0, Source.A lot of gardeners shoot themselves in the foot by continually weeding their beds, effectively creating conditions where annual weedy plants thrive. Some plants, such as common groundsel (Senecio vulgaris) or hairy crabweed (Fatoua villosa) have such a short lifecycle, able to complete as many as 5 generations per growing season, that they are actively encouraged by frequent weeding. It is nearly impossible to keep up with these plants, because they are specifically adapted to frequent weeding and tilling, and they have often already produced seed by the time people notice them. Instead, they can be kept out by allowing perennial groundcovers to cover all exposed soil.

Natural disturbances can interact with the management of gardens and other landscapes. A typical yard will have its wet and dry spots. If you plant a flood-intolerant plant in a depression that perodically floods, it will die. Similarly, if you plant a drought-intolerant plant on a dry site, it will die unless you go out of your way to water it during droughts, and such watering can be costly and wasteful. Similarly, browsing pressure from mammals such as rabbits, deer, or groundhogs, can kill certain plants, especially those most palatable to these herbivores, whereas others, the more toxic and bitter-tasting ones, or ones with other defenses such as thorns or stinging hairs, will be more resistant. Intelligent, sustainable gardening demands knowing both the natural and managed disturbances your yard will be subjected to, and selecting the right plants to withstand those challenges.

Disturbance in Ecological Restoration Work

Understanding disturbance is key to doing ecological restoration work for multiple reasons. Every site has its particular unique set of disturbances that it experiences. A floodplain may experience regular deep, fast-moving flooding, but may rarely experience drought or fire. An upland site, however may experience more frequent drought, and some may experience occasional wildfire. An exposed hilltop may be more exposed to high winds, whereas coastal dunes are prone to salt spray, storm surge, and shifting sands.Semi-wild habitats can bring additional anthropogenic disturbances. A meadow under a power-line right of way may be subjected to periodic mowing and/or herbicide application. Sites adjacent to an area (such as cropland or railroad tracks) with heavy herbicide use may be subjected to occasional, irregular herbicide drift from the neighboring site. Highways and urban roadsides may have runoff from road salt in winter. A creek running through cropland may have nutrient pollution from agricultural fertilizers and resulting algal blooms, and a creek running through a formerly mined area may have acid mine drainage. And in general, waterways downstream from areas where land has been cleared and/or paved, and wetlands drained, will tend to experience more severe oscillations of water levels (including both flooding and drought) than natural watersheds with the vegetation cover intact.

Anthropogenic edge habitats are semi-wild habitats that are widespread around human habitation. Here, a wild forest transitions to mowed grassland in a park. The maintenance of the edge creates disturbance through weedwhacking, bushhogging, pruning, and/or herbicide use. The absence of woody plants in the foreground provides evidence that this site experiences regular disturbance that removes all woody plants from within a few feet of the edge. Farther back, shrubby growth and perennial vines but no large trees shows that, within several years, a disturbance removed all woody plants a few feet farther back, but that woody plants have been allowed to grow up since then.

Anthropogenic edge habitats are semi-wild habitats that are widespread around human habitation. Here, a wild forest transitions to mowed grassland in a park. The maintenance of the edge creates disturbance through weedwhacking, bushhogging, pruning, and/or herbicide use. The absence of woody plants in the foreground provides evidence that this site experiences regular disturbance that removes all woody plants from within a few feet of the edge. Farther back, shrubby growth and perennial vines but no large trees shows that, within several years, a disturbance removed all woody plants a few feet farther back, but that woody plants have been allowed to grow up since then.Understanding the interplay between the management strategies and species present along the edge is key to controlling invasives and promoting native plant biodiversity in an edge habitat like this. Restoration techniques can involve the seeding or transplanting of new plants in, removal of invasives, and changing of the management regime.

Photo © Alex Zorach, CC BY-SA 4.0.

When re-vegetating a site, or seeding or transplanting plants in to re-establish the native flora or increase biodiversity, in order for the plants to persist long-term, plants must be chosen that are adapted to the site's disturbance patterns. In order to match a plant to the site, one must understand both the plants and the site.

Keep in mind that the disturbance regime is likely to have changed, so just because certain plants thrived on a site historically does not mean that it will always be possible to reestablish them. Some examples of why it may not be possible to restore the historic flora on a site include:

- Areas upstream in the watershed may have been cleared, leading to more severe flooding and/or water table oscillation.

- Topsoil may have been lost, degraded, or compacted, leading to lower water percolation into the soil and thus worsening of drought.

- Clearing of forests or trees on adjacent sites may expose the site to higher winds and more extreme temperatures.

- Anthropogenic disturbances, such as controlled burns, practiced by indigenous people may have been halted, and may not be legal and/or practical to bring back to the site.

- The site may face greater herbivory pressure, such as from deer overpopulation in suburban areas, or less herbivory, such as in areas of the Great Plains where bison have been extirpated.

- The climate may have changed in such a way that the habitat is now suited for different species than what originally grew there.

- The site may be subjected to new anthropogenic disturbances, such as herbicide, mowing, weedwhacking, or foot traffic or other use.

In meadows mowed once a season, changing of the timing of mowing can favor certain vegetation over others. When meadows are dominated by non-native cool-season grasses such as this orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata), timing of mowing in spring, after they emerge but before seed matures, will reduce them and create space for the germination, establishment, and emergence of native warm-season grasses such as yellow indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), as well as native warm-season perennials such as tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima).

In meadows mowed once a season, changing of the timing of mowing can favor certain vegetation over others. When meadows are dominated by non-native cool-season grasses such as this orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata), timing of mowing in spring, after they emerge but before seed matures, will reduce them and create space for the germination, establishment, and emergence of native warm-season grasses such as yellow indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), as well as native warm-season perennials such as tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima).Alternatively, switching from mowing to a controlled burn regime may achieve a similar effect, in some cases even more effectively. However, such changes must be site-specific. On a site with fire-intolerant native plants and fire-tolerant invasives, fire would be harmful. And on a site with invasive warm-season grasses and native cool-season grasses, timing mowing later, to allow the cool-season grasses to mature and then cut the warm-season grasses before they set seed, might be optimal.

Photo © Brandon Corder, CC BY 4.0, Source.

The disturbances in our world will continue to change, both for natural reasons and through the actions of humans. We will achieve better results when we learn to work with these disturbances, picking plants able not only to withstand them, but to exploit or benefit from them.

Although greater knowledge can lead to better matching of plants to the site, there is no substitute for trial-and-error, which can be seen as the human side of the process of natural selection, a process that is always at work in wild ecosystems and is a large part of how plants evolve and adapt to their environment. We emphasize that, even with the articles on our site that are more-or-less "complete", research is best used only as a starting point. The vision of our site is that it will lead to real-world restoration efforts, and those efforts will inevitably involve experimentation and ongoing observation to figure out which methods work best.

Thank you!

Thank you to everyone who has read to the end of this lengthy post, for caring enough about these issues to do so. Thank you to everyone who takes the information in this post out into the world to do ecological restoration work. Thank you to everyone who pays attention to plants and observes their behavior in the real world enough to notice their different responses to disturbance. And thank you also to all the donors who continue supporting our work on this site!What "Native" or "Introduced" Mean: Myths and Misconceptions

March 11th, 2025 by Alex Zorach

One of the most important aspects of our site is our classification of plants as either Native, Introduced, or Expanded in a particular region.Unfortunately, "native" can sometimes become a bit of a buzzword. We previously wrote about common problems with nursery-grown plants which addressed some ways in which harm can come even when people buy and plant native plants. Now, we challenge other misconceptions about what it means for a plant to be native (or introduced.) Although, the general trend is that favoring native plants tends to be beneficial, there are exceptions and also other factors to consider.

Native Plants

We define a plant as native in North America if it was present at the time of European colonization. In order to make a relatively objective definition of the term "native", it is necessary to pick some sort of time cutoff. European colonization of North America was the point at which rapid changes to North America's ecosystem began, and a point after which a large number of species were introduced from other continents, so it is the best choice for a cutoff.Why does the concept of "native" matter?

The basic idea behind native plants is that because they have been present in an ecosystem for a long time, the ecosystem has had time to adapt to their presence. Herbivores, including specialist insects, have evolved to eat the plant, and these herbivores in turn support animals higher up on the food web. Fungi and other detrivores have evolved to break down litter and dead material from the plant. Other plants have also had time to adapt to the plant's presence, tolerating things like any allelopathy (chemical inhibition of plant growth) as well as competition for light, water, and nutrients. The result is a community of organisms that is able to coexist in relative balance.Native does not mean that a plant has always been here.

A plant that we classify as native, but is relatively new to North America in geologic time, is yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus). This plant is generally thought to have colonized North America, possibly from tubers floating on ocean currents, a few thousand years ago. We consider it native because it was present at the time of European colonization.Non-native does not mean that a plant was never here.

Trees like the Dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), frequently planted in landscaping, grew in North America millions of years ago. This plant is considered introduced because it died out here and was reintroduced long after European colonization. Photo © Justin Flint, CC BY 4.0, Source.

Trees like the Dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), frequently planted in landscaping, grew in North America millions of years ago. This plant is considered introduced because it died out here and was reintroduced long after European colonization. Photo © Justin Flint, CC BY 4.0, Source.A plant that was once found in North America, but was locally extirpated long before European Colonization, is the dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides). The dawn redwood, or at least trees like it, once grew across the entire northern hemisphere, evidenced by its presence in the fossil record. These trees were thought extinct, with the most recent records dating to 150 million years ago. But in the 1940's, an extant population was discovered in a remote part of China. We consider this tree non-native, even though it once occurred here, because it was not present at the time of European colonization.

Keep in mind too that saying "this plant was present in North America 150 million years ago" is an oversimplification. Speciation, the process through which plants evolve into separate species, can occur on much shorter timescales than 150 years, and we also don't know how much the historical dawn redwoods found here differed from the extant ones sourced from China. This uncertainty reinforces that "Introduced" is the correct label for such plants.

Native does not always mean good for the ecosystem.

Although in most cases, protecting native plants is a worthwhile goal, it is not always good to have a plant increase in numbers just because it is native. In some cases, human alterations to the environment can increase the numbers of a particular native plant in ways that cause catastrophic changes.An example would be the eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) in the Great Plains. Redcedars have the unusual combination of being both drought-tolerant and fire-intolerant, which naturally limited them to upland sites protected from fire, usually due to some combination of topography and soil conditions. They naturally occurred in habitats like limestone and serpentine barrens, granite outcroppings, and sandstone cliffs, where the thin, rocky soil prevented the accumulation of enough litter to cause a fire. Drier sites would have burned regularly, killing them when young, and instead supporting either open prairie (in the western portion of the Great Plains) or savanna with a mix of grasses and fire-tolerant trees such as oaks (in the eastern border of the Great Plains where they transition to the Eastern Deciduous Forests, such as the Cross Timbers region.)

Fire suppression by humans, both intentional, and unintentional through building roads which act as firebreaks, has led eastern redcedar to colonize deep-soil habitats in the Great Plain where it would not have naturally occurred. These changes can threaten grassland and savanna ecosystems and the species that depend on them.

This eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) is growing in Norman, OK, in a broader region where it is technically native, but was restricted to specialized habitats. It is now moving onto sites like this one, where it normally would have been excluded by fire. It then shuts out fire-tolerant vegetation such as the little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) growing in the foreground. Photo © Gaudaceous Cress, CC BY 4.0, Source.

This eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) is growing in Norman, OK, in a broader region where it is technically native, but was restricted to specialized habitats. It is now moving onto sites like this one, where it normally would have been excluded by fire. It then shuts out fire-tolerant vegetation such as the little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) growing in the foreground. Photo © Gaudaceous Cress, CC BY 4.0, Source.Redcedar obviously shuts out grasses by shading them out. But it can indirectly kill even large trees. The presence of redcedar in a savanna or oak woodland provides a "ladder" through which ground fires can spread into the canopy. Redcedar also suppresses low-intensity ground fires in a normal year, which leads to greater fuel accumulation than would occur in a situation where ground fire were more frequent. The combination of greater fuel accumulation and the "fire ladder" can increase the risk of severe crown fires during prolonged droughts. These fires, which would have been rare naturally, can kill the normally fire-resistant canopy trees. They also threaten humans, as they are more likely to spread over large areas and consume homes than low-intensity ground fires that burn out quickly and are easily contained. You can read more about this dynamic in the OSU extension's article on Eastern Redcedar and Climate Change in Oklahoma’s Cross Timbers Forests.

Native does not always mean a plant supports more insects.

Although there is a strong trend that native plants tend to support far more insects than non-native ones, there are exceptions. A common example is American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana). In the eastern US, this species is the only member of Phytolaccaceae, a mostly-tropical-to-subtropical family. Among insects, it is eaten mostly by generalist herbivores, contrasting with native species such as the goldenrods (Solidago sp.) which have their center of global biodiversity here in North America, and support an extraordinary variety of insects, both specialists and generalists. American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) is native to the eastern US, but supports few specialist insects. Photo © nealkelso, CC BY 4.0, Source.

American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) is native to the eastern US, but supports few specialist insects. Photo © nealkelso, CC BY 4.0, Source.This is not to say pokeweed is bad; it supports wildlife in numerous other ways such as birds and mammals eating its fruit and seeds, and stabilizes soil in disturbed areas. And it often competes against disturbance-loving invasive plants such as common mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) or creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense).

Introduced Plants

We consider a plant introduced if it was not present in a region at the time of European colonization of North America, and if it has become established in an area discontiguously with its native range. The most common examples of introduced plants are ones introduced from Eurasia; less commonly there are plants introduced from South or Central America into the US or Canada, or introduced across a major geographic divide between the East and West coasts. Although most introduced plants are native to other continents, there are several examples of species introduced from one coast of North America to the other, such as this American sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), native to the east but introduced in California. Photo © Amelia Tauber, CC BY 4.0, Source.

Although most introduced plants are native to other continents, there are several examples of species introduced from one coast of North America to the other, such as this American sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), native to the east but introduced in California. Photo © Amelia Tauber, CC BY 4.0, Source.One key reason that it is relevant whether or not a plant is introduced is that, because of the large separation from their native range, introduced plants tend not to bring specialist herbivores with them, and as such, they tend to support the food web much less than native plants. In the case of introduced plants that reproduce and grow vigorously, the lack of natural herbivores can give these plants a competitive advantage over native plants, making it more likely that they become invasive.

Introduced does not mean invasive.

A plant is said to be invasive if it establishes in a new environment where it was not naturally found, and it causes major harm to the ecosystem in that environment. Money plant (Lunaria annua) is related to garlic mustard and dame's rocket (Hesperis matronalis), and is introduced in North America, but is nowhere near as damaging ecologically as those other plants. Photo © Jon Sullivan, CC BY 4.0, Source.

Money plant (Lunaria annua) is related to garlic mustard and dame's rocket (Hesperis matronalis), and is introduced in North America, but is nowhere near as damaging ecologically as those other plants. Photo © Jon Sullivan, CC BY 4.0, Source.Only a small portion of introduced plants ever become invasive. In fact, an overwhelming majority of introduced plants struggle and only establish in a small region and/or specific habitats, where they are usually far from dominant. However, when introduced plants become invasive, they are much more likely to lead to collapse of the food web. Countless examples abound, some of the worst being garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Norway maple (Acer platanoides), english ivy (Hedera helix), and Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica).

Just because an introduced plant has not become invasive does not mean it will never become invasive.

People who rightfully recognize that most introduced plants do not become invasive often overcompensate, disregarding warranted caution in ways that leads plants to become invasive. The phenomenon of a plant becoming invasive is not always passive: active, widespread planting by humans, and breeding of new cultivars, often through combining genetic material from different source populations, which increases vigor of plants, can lead plants to become invasive.Examples of plants that initially did not grow well in North America, but became invasive after they were widely planted include kudzu (Pueraria montana), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and Lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria). Kudzu was widely planted in southern agriculture for years before it became invasive. Japanese honeysuckle was used both as a garden plant and widely planted to increase deer populations for hunters. Lesser celandine was widely planted as a garden plant, starting in the 1860's, valued for its pretty yellow flowers, but it did not explode in numbers until the 1990's, and even then did not reach its full extent until the 2000's or later.

lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) is one of many examples of a plant that was cultivated in gardens for over 100 years before becoming invasive in most regions where it is now invasive. Photo © , CC BY-SA 4.0.

lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) is one of many examples of a plant that was cultivated in gardens for over 100 years before becoming invasive in most regions where it is now invasive. Photo © , CC BY-SA 4.0.The bottom line is that caution is always warranted when growing introduced plants. There is always some risk of plants becoming invasive, and this risk increases dramatically when different cultivars are being developed by breeding plants from different source populations in their native range.

Expanded Plants

"Expanded" is our novel category that we coined. It was loosely inspired by BONAP's use of the label "adventive" to describe plants native somewhere in North America but introduced elsewhere, but our term does not mean the exact same thing that BONAP does with "adventive". We say a plant is expanded if it is not native to a region, but its new range is connected to or contiguous with its native range, typically if it is separated only by smaller gaps not much larger than those that occur in its native range. The reason we use continuity, and not establishment method (i.e. garden escapes vs. natural spread) as the criterion for labeling something "expanded", is that continuity with the native range affects whether or not specialist insect herbivores are able to expand their range to find (and eat) the new populations. This late boneset (Eupatorium serotinum) plant is growing in southeast PA, a region where we label this plant Expanded. Because this area is connected to the plant's native range, the insects that feed on it have come with it, not only pollinators like this butterfly, but also herbivores feeding on the leaves, as evidenced by the bites taken out of the leaves. Photo © Kristy Morley, CC BY 4.0, Source.

This late boneset (Eupatorium serotinum) plant is growing in southeast PA, a region where we label this plant Expanded. Because this area is connected to the plant's native range, the insects that feed on it have come with it, not only pollinators like this butterfly, but also herbivores feeding on the leaves, as evidenced by the bites taken out of the leaves. Photo © Kristy Morley, CC BY 4.0, Source.As such, expanded plants function more like native plants ecologically, at least with respect to their integration into the food web. Expanded plants contrast with introduced plants, which tend to be poorly integrated into the food web.

Some examples of expanded plants include late boneset (Eupatorium serotinum), which has expanded northward, or the common sunflower (Helianthus annuus), which has expanded eastward. Numerous factors can contribute to range expansion. Global warming pushes plants northward and to higher elevations. The clearing of forests and creation of more open habitats through roads, agriculture, and creation of industrial waste ground, has created habitat for more drought-tolerant, sun-loving western plants to expand eastward.

Expanded does not mean non-invasive.

Expanded plants are much less likely to become invasive, because they bring their specialist insect herbivores with them. These insects both help to keep them in check, and ensure they support the food web. However, insect-resistance or lack of natural herbivores is only one mechanism through which invasive plants can become dominant, and collapse of the food web is only one mechanism through which they can cause harm. Thus plants that expand adjacent to their native range can still become invasive. This black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) is growing in Ottawa, Ontario, a region where we mark it as Expanded, but it is considered to be invasive in this region. Photo © Jean Sorensen, CC BY 4.0, Source.

This black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) is growing in Ottawa, Ontario, a region where we mark it as Expanded, but it is considered to be invasive in this region. Photo © Jean Sorensen, CC BY 4.0, Source.An example of such a plant is the black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), widely agreed-on to be native to the Appalachians from northern AL and eastern TN, northeast through western PA and southeastern Ohio. It has, however, expanded in all directions and is now found the whole way west to the West Coast, south to the Gulf Coast, and north through New England and into Canada. The insect specialists, such as the locust borer beetle (Megacyllene robiniae), that eat it have come with it and can be found throughout its new range.

Black locust is considered invasive in New England and Canada, where it colonizes habitats which are not adapted to the presence of as large and efficient a nitrogen-fixer as it. Its presence alters these ecosystems, threatening plants adapted to lower-nitrogen conditions, and facilitating the growth of other invasive plants that are not eaten by as many insect herbivores, so it indirectly causes a similar food web collapse as species introduced from other continents. People wishing to learn more may want to read the Ecological Landscape Alliance's article on Black Locust in New England, or the Ontario Invasive Plant Council's Document on Black Locust (PDF).

Using This Knowledge as a Starting Point

We hope the takeaway here is that the labeling of a plant as native, introduced, or expanded is a key piece of information in determining the effect that plant will have on an ecosystem. But it is not a substitute for a more thorough understanding of that plant's ecology.Using these categories is thus a useful first step or filter in choosing what to do with plants. For example, in choosing plants for a garden or ecological restoration project, it makes sense to limit your search to plants native to your local region, perhaps also considering expanded plant in some cases. However, not all of these plants will be suitable, and some of them may even be problematic plants that you want to avoid or remove for various reasons.

Similarly, if identifying volunteer plants or surveying a wild area to come up with a management plan, it makes sense to be wary of introduced plants, as any introduced plant that grows vigorously on its own is likely to be invasive. However, it is important to prioritize, and it does not always make sense to expend resources to remove plants just because they are introduced.

As we complete more plant articles, you can find more detailed information in these articles. The "control" section of articles not only gives information about how to control invasives, but also tells you scenarios where it is relatively more or less important (or even unnecessary or harmful) to control a particular species. We also want to thank our donors, small and large alike, that make the continued work on the site possible and help us to complete more of these articles.

Smarter & More Informative Search Results

January 13th, 2025 by Alex Zorach

Users have requested we make our search "smarter", and we are pleased to announce progress on this front. Last summer we announced search improvements that return unlinked records to external websites when a scientific name search returns no results. Behind-the-scenes, this system has been notifying us of the searches so we can interlink the corresponding records after resolving any taxonomic disparities. This process has taken a lot of time and work but is already yielding results, as we are seeing fewer unmatched searches over time.Today we announce a more visible improvement. When typing in a scientific synonym or alternate common name, our search not only matches synonyms and alternate names, but shows which record each matched name points to. The notation involves multiple lines: the first line shows the record matched in our system, with the accepted scientific name in our treatment; next to this name is the authority (original author) of the accepted name. The second line shows the match to the search query, a different name that refers to the same taxon under our treatment. An arrow pointing up shows which synonym points to which record.

The Same Scientific Name Can Point To Different Species

Note that searches for a single name may return multiple records because different authors may use the same name to refer to different taxa. Our search improvements aim to concisely communicate these relationships.Here is an example:

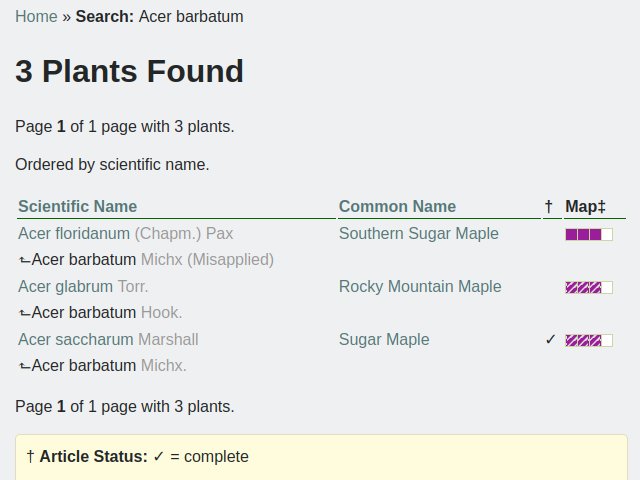

This screenshot shows the results when the scientific name Acer barbatum is typed into the search box. This name is not accepted under our treatment, but rather, is treated as a synonym of three different species, depending on which author's use of the name is referenced. The name has been coined by two authors, William Jackson Hooker (abbreviated Hook) and André Michaux (Michaux). Hooker used the name to describe a specimen which was later found to be the already-described Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum), whereas Michaux did the same for sugar maple (Acer saccharum). However, Michaux's name was misapplied for years to refer to southern sugar maple (Acer floridanum) and this usage may actually be the most widespread.

This screenshot shows the results when the scientific name Acer barbatum is typed into the search box. This name is not accepted under our treatment, but rather, is treated as a synonym of three different species, depending on which author's use of the name is referenced. The name has been coined by two authors, William Jackson Hooker (abbreviated Hook) and André Michaux (Michaux). Hooker used the name to describe a specimen which was later found to be the already-described Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum), whereas Michaux did the same for sugar maple (Acer saccharum). However, Michaux's name was misapplied for years to refer to southern sugar maple (Acer floridanum) and this usage may actually be the most widespread.If you click on any of these articles, the top of the article will show taxonomy notes clarifying relevant details in more depth.

If you are having trouble resolving author names, you may find Wikipedia's List of botanists by author abbreviation helpful.

Searching for Species That Have Been Split

The yellow pond lily is one species that has been split, such that what was once referred to by the name Nuphar lutea is now referred to by various names. The plant pictured here is spatterdock (Nuphar advena); if you look closely there is a large friend under the water utilizing the same habitat. Photo © Zach E Plants, CC BY 4.0, Source.

The yellow pond lily is one species that has been split, such that what was once referred to by the name Nuphar lutea is now referred to by various names. The plant pictured here is spatterdock (Nuphar advena); if you look closely there is a large friend under the water utilizing the same habitat. Photo © Zach E Plants, CC BY 4.0, Source.In some cases, a species has been split, and what were formerly considered to be sub-taxa of a single species (such as varieties or subspecies) are now considered to be separate species. The search now does more-or-less the same thing for the sub-taxa, showing which names point to which species. The return of multiple records in this case is important, because a person searching for a particular name might not know that the taxon referred to by the name has been split in our treatment.

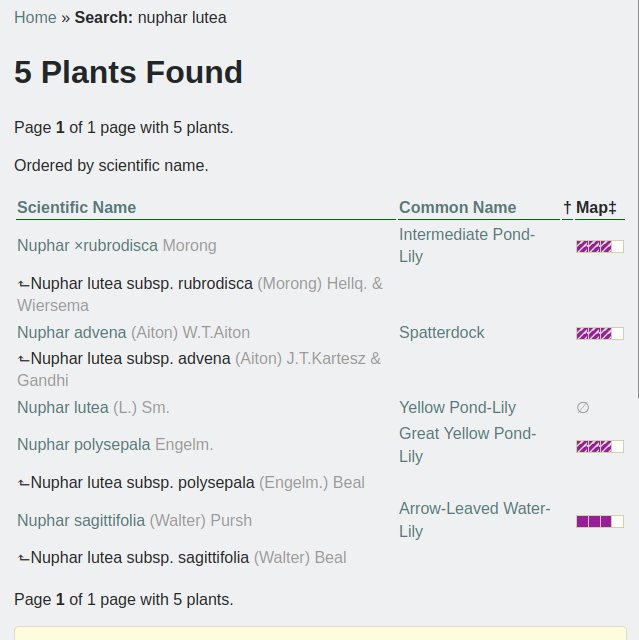

An illustrative example of a multi-way split is seen in this search for Nuphar lutea:

Nuphar lutea is universally-agreed to refer to the species yellow pond-lily (Nuphar lutea). However, previously, this species was thought to include populations all around the Northern Hemisphere, in both North America and Eurasia. Recent work split it into numerous different species, with what were formerly considered subspecies now treated as proper species. The original name now only refers to a Eurasian species that does not occur in North America.

Nuphar lutea is universally-agreed to refer to the species yellow pond-lily (Nuphar lutea). However, previously, this species was thought to include populations all around the Northern Hemisphere, in both North America and Eurasia. Recent work split it into numerous different species, with what were formerly considered subspecies now treated as proper species. The original name now only refers to a Eurasian species that does not occur in North America.Our search not only matches this species (with a stub article explaining the split) but also four former subspecies, pointing to the respective species they have been renamed to.

Yet another phenomenon that our search matches in this manner are misspellings and alternate endings. Alternate endings in scientific names are common because the names are in Latin, and the conventions for naming can sometimes cause disagreement between declension and/or grammatical gender (of which Latin has 3.) Authors fluent in Latin will occasionally "correct" a name, which then conflicts with the conventions of taxonomy, in which the oldest name is accepted. One such example is betatakin fiddleleaf (Nama retrorsum), where the mismatched name is the accepted one, but the "corrected" name Nama retrorsa where the genders match is more widely used. Alternate endings are also common in third-declension nouns, because the gender is not as clear from the noun itself, such as how flax-leaved stiff-aster (Ionactis linariifolia) is also referred to as Ionactis linariifolius. In some cases, the accepted name has matched genders, but people sometimes use alternate names with mismatched genders anyway, such as with piedmont leather-root (Orbexilum lupinellum), where the mismatched name Orbexilum lupinellus is in widespread use.

The genus for flax-leaved stiff-aster (Ionactis linariifolia), Ionactis, is a third-declension Latin noun; unlike the first-declension nouns ending in "-a" (feminine) "-us" (masculine) or "-um" (neuter), the grammatical gender of such nouns is not immediately clear, and as such, people often use alternate endings on the epithets of scientific names, which are adjectives to describe the nouns, here linariifolia, which means the leaves resemble those of the Linaria genus. Photo © Todd Boland, CC BY 4.0, Source.

The genus for flax-leaved stiff-aster (Ionactis linariifolia), Ionactis, is a third-declension Latin noun; unlike the first-declension nouns ending in "-a" (feminine) "-us" (masculine) or "-um" (neuter), the grammatical gender of such nouns is not immediately clear, and as such, people often use alternate endings on the epithets of scientific names, which are adjectives to describe the nouns, here linariifolia, which means the leaves resemble those of the Linaria genus. Photo © Todd Boland, CC BY 4.0, Source.Besides alternate endings, other common misspellings include adding or omitting an "i" or "a" (mac/mc) or hyphens, or exchanging "ae" for "oe" or "i" for "y". Some such examples include pecan (Carya illinoinensis) being misspelled Carya illinoensis (missing "i"), tufted evening primrose (Oenothera caespitosa) being misspelled Oenothera cespitosa, or the stansbury cliffrose (Purshia stansburiana) being misspelled Purshia stansburyana.

We do not exhaustively list all possible mispellings and typos; our site does not perform a "fuzzy search", and part of the reason why is that we want you to be able to be certain when a search does not return anything, a limitation of approximate search matches that can make it hard to figure out when a certain record does not exist. If you type an exact name into our search, and no results are returned, you can be certain that there is no corresponding record by that name. However, we are trying to list as many misspellings and alternate endings as we can, whenever they have been published. Keep in mind our listing of these alternate entries is an ongoing process and is far from complete; we are focusing on the more commonly-used ones first to maximize utility. If we find such a spelling or ending in any published source and bring it to our attention, we will add it.

Tip For Searches When Uncertain of Spelling

Our search functions differently from a typical web search, in that it does not split the search into words. Understanding the differences can help you use it more effectively, as it can do some things that a typical web search cannot do.The search returns only exact matches to what you type in, but it does return matches to incomplete names. Thus if you are uncertain of some aspect of the spelling, an easy way to search is to leave off the portion of the name you are uncertain about. For example, suppose you have trouble spelling the genus "Symphyotrichum"; you can easily locate this genus in your search by typing in the first few letters "Sym" and then you can find the correct spelling in the results, and copy-and-paste this, or just remember it. You can also use these sorts of truncated searches to save time. For example, if searching for the unwieldly crookedstem aster (Symphyotrichum prenanthoides), you can type in only "um pre" and it will return this species (and in this case only this species, believe it or not!)

Note however that the search must only be truncated at the beginning or end of the full search string. If you type in "Sym pre" it will not match anything.

Alternate Common Names Are Matched Similarly

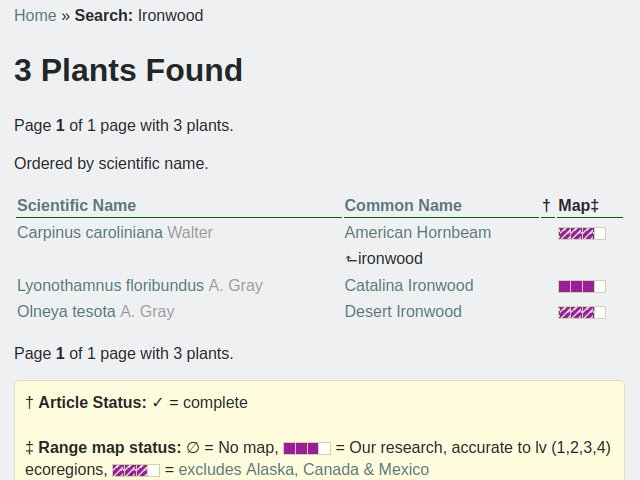

The features above are richest for scientific names, but we have also implemented the same type of matching for common names. As we explained last spring, we give preference to better common names when possible, while retaining older, problematic names as well as adding as many alternate names as we can find. This screenshot shows a search for "ironwood", which can refer both to the American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) as well as two West-Coast species, the Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus) and desert ironwood (Olneya tesota).

This screenshot shows a search for "ironwood", which can refer both to the American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) as well as two West-Coast species, the Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus) and desert ironwood (Olneya tesota).As with the rest of our site, the search is a work-in-progress, so it will get better as we continue adding alternate names.

We are grateful to all our donors who help support this work along with all of the other aspects of our site. This post only covers one of many things we have been working on lately. Other highlights include that we have begun publishing goldenrod (Solidago) ID guides, we have built hundreds of more range maps, completing many of them into Canada and Alaska, and we have also added the ability to credit authors/coauthors, reviewers, editors, and other contributors on our articles, laying the foundation for more people to contribute to our site. We hope to publish more posts on other updates soon.

For now, enjoy the improved search!

The aforementioned American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), also known as musclewood, blue beech, and ironwood, now not only appears in searches for these names, but the search clearly denotes which name was matched, and that it is pointing to this species. Photo © Katja Schulz, CC BY 4.0, Source.

The aforementioned American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), also known as musclewood, blue beech, and ironwood, now not only appears in searches for these names, but the search clearly denotes which name was matched, and that it is pointing to this species. Photo © Katja Schulz, CC BY 4.0, Source.Archive of All Blogs

Disturbance and its Role in Plant Habitat Preferences, May 29th, 2025

What "Native" or "Introduced" Mean: Myths and Misconceptions, March 11th, 2025

Smarter & More Informative Search Results, January 13th, 2025

The Effect of the 2024 US Election on Plant Biodiversity and bplant.org, October 30th, 2024

The Problems With Nursery-Bought Plants, And The Solutions, October 8th, 2024

More Databases Linked & Search Improvements for Scientific Names, July 9th, 2024

Choosing The Best Common Names For Plants: Challenges & Solutions, April 19th, 2024

Range Map & Taxonomic Update Progress, January 31st, 2024

Giving Thanks To Everyone We Rely On, November 22nd, 2023

Thinking More Deeply About Habitat, April 5th, 2023

2022 Year-End Summary: Successes & New Goals, February 15th, 2023

New Databases Linked: Flora of North America & NatureServe Explorer, November 11th, 2022

All Range Maps 2nd Generation, Taxonomic Updates, & Fundraising Goal Met!, September 29th, 2022

More Range Map Improvements, POWO Interlinking, And Notes Fields, June 7th, 2022

Ecoregion-Based Plant Lists and Search, March 30th, 2022

Progress Updates on Range Maps and More, February 10th, 2022

The Vision for bplant.org, December 9th, 2021

New Server: Software & Hardware, August 30th, 2021

More & Improved Plant Range Maps, July 19th, 2021

A Control Section for Invasive Plants, April 15th, 2021

Progress Bars & State Ecoregion Legends, March 11th, 2021

Our 2020 Achievements, February 9th, 2021

Interlinking Databases for Plant Research, November 11th, 2020

A New Homepage, Highlighting Our Articles, July 29th, 2020

A False Recovery, But North Carolina's Ecoregions are Complete!, June 9th, 2020

We're Back After COVID-19 Setbacks, April 3rd, 2020

Help Us Find Ecoregion Photos, February 27th, 2020

What We Achieved in 2019, December 30th, 2019

Plant Comparison and ID Guides, October 30th, 2019

We Are Now Accepting Donations, October 14th, 2019

US State Ecoregion Maps, New Footer, Ecoregion Article Progress, and References, September 19th, 2019

Tentative Range Maps of Native Plants, August 12th, 2019

Ecoregion Locator and Interactive Maps, July 10th, 2019

Using Ecoregions Over Political Boundaries, May 13th, 2019

How We Handle Wild vs Cultivated Plants, April 16th, 2019

A Blog To Keep People Updated On Our Progress, April 8th, 2019

Sign Up

Want to get notified of our progress? Sign up for the bplant.org interest list!